The first person hired at a demand forecasting firm needs to be a brilliant data scientist. That’s absolutely what we did at Amperon in 2018. But our second hire might surprise you.

It was a NASA-trained meteorologist. In this Q&A, Dr. Mark Shipham explains why accurate weather forecasting is so important to accurate demand forecasting. Plus, he describes how Amperon’s approach to weather data is different from other demand forecasting firms and why now is an exciting time to be in the field.

For starters, why is meteorology so important to electricity demand forecasting?

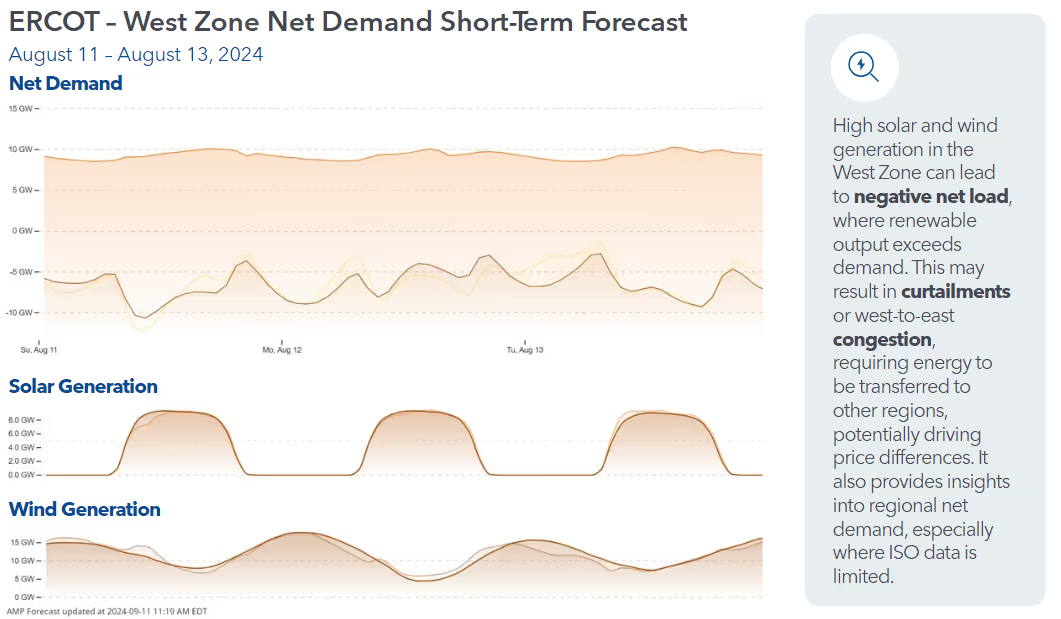

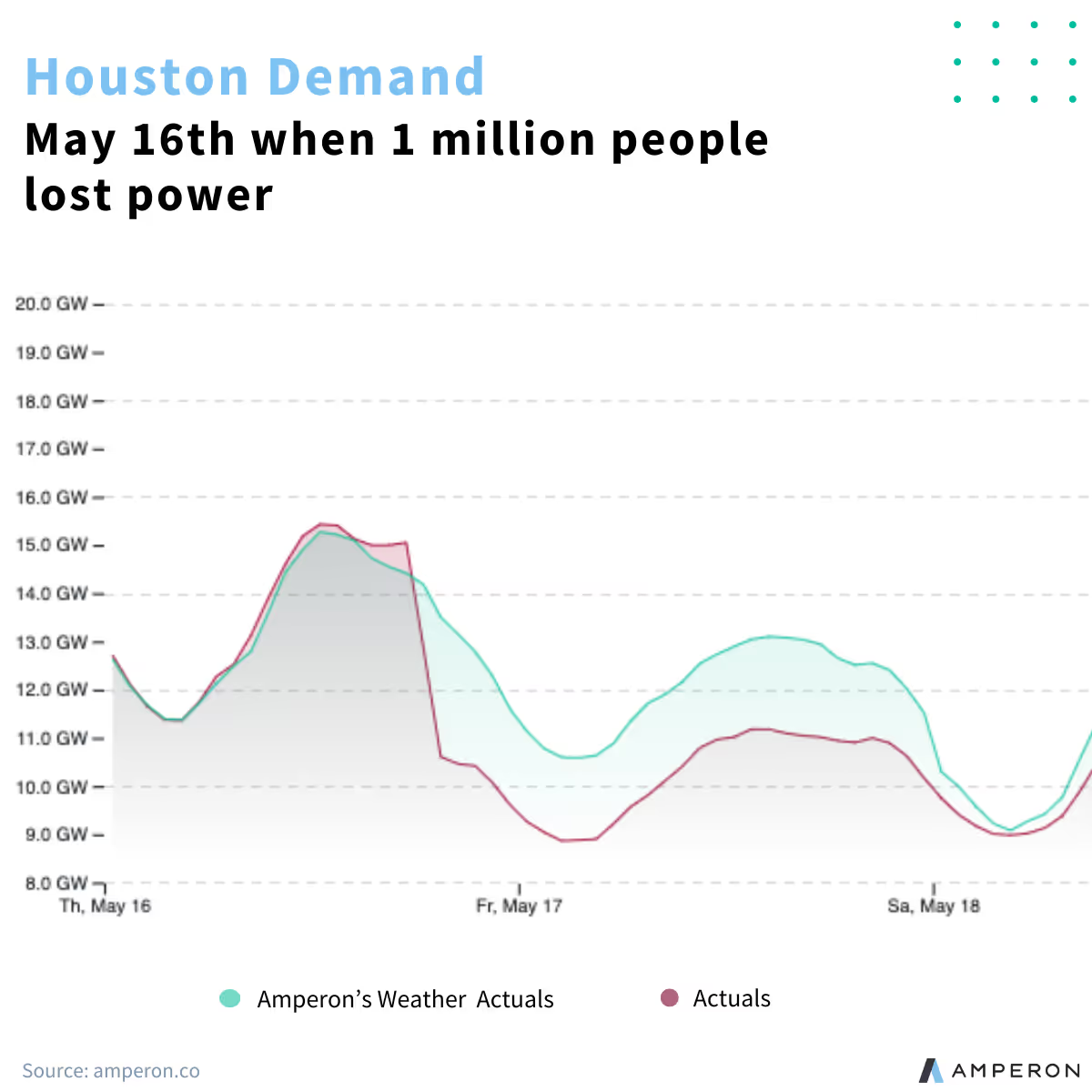

Shipham: There's a very strong correlation between weather and demand. For instance, recently the weather forecasts predicted 103 degrees in Dallas and 100 degrees in Houston. So, it was very likely they would also have record-high power demand to run all the air conditioners in the region, and real-time electricity prices would shoot from $50 to $5,000 per megawatt hour.

No one wants to get stuck buying electricity on the spot market at prices like that, so retail energy providers (REPs) and traders need accurate weather forecasting to help them predict how much electricity to purchase in advance. In short, that’s what demand forecasting is, and if you have bad weather inputs, your demand forecasts will be wrong — garbage in, garbage out. That can be catastrophically bad for business.

Most people probably don’t associate meteorologists with energy companies. How did you come to be at Amperon?

Shipham: Our CEO, Sean Kelly, jokes that I was born a meteorologist, and I suppose he’s right. I began keeping a weather journal in second grade, which is probably unusual for a seven-year-old.

After getting a master’s degree in meteorology, I chose to work at NASA. The pay was low, but the experience was incredible. I got to travel all over the world, studying wildfires in Canada, deforestation in the Amazon, and air pollution in Asia. While at NASA, I was also fortunate to earn my PhD under Bob Harris at the Earth Ocean Sciences Department he founded at the University of New Hampshire. Then after 15 years with the agency, I jumped into energy trading, which was taking off with deregulation. I worked for Dominion Energy for a few years, then Morgan Stanley in New York, and eventually EON, where I met Sean. For about 12 years, I worked closely with energy traders like him, advising their positions — and giving them someone to blame when their trades went wrong (laughs)! But I came to think the world of Sean, and when he asked me to join Amperon, I knew it was the start of a good thing.

So, what are your responsibilities at Amperon?

Shipham: In the early days, I advised our computer science team. They’re masters of artificial intelligence, but at the time they didn’t know much about weather data. So, I helped them understand the different variables and how to weight them in the machine-learning models they developed.

But now my role is primarily client facing. I produce daily weather updates, drawing out the data from our platform that clients want to pay careful attention to — like heating or cooling degree days, or wind-speed forecasts. I hold weekly calls and webinars with clients who have questions or want weather-related advice, and I produce seasonal forecasts to help clients consider demand strategies that reach beyond the near term.

The other big part of what I do is confirm our weather inputs on a daily basis. Weather forecasts are pretty good — and getting better all the time. But they can be off in ways that have significant impact on demand. Arctic cold fronts, for example, almost always come through faster than the models predict. Also, small mesoscale storms are another example. Radars don’t always pick them up so well, and they can affect temperatures.

So, each morning I review what we’re getting from our different weather vendors and what it means for ERCOT, PJM and the other markets where we have customers. If there’s a discrepancy, I alert our team to make sure it’s resolved or handled accordingly.

What are the weather inputs that Amperon uses?

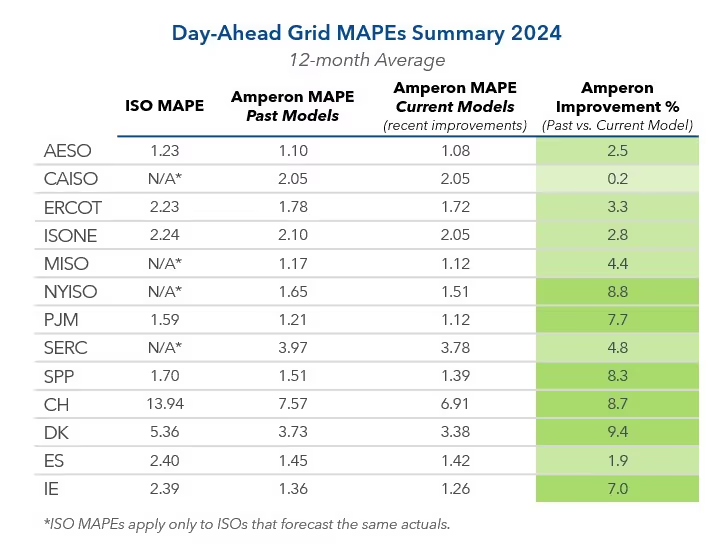

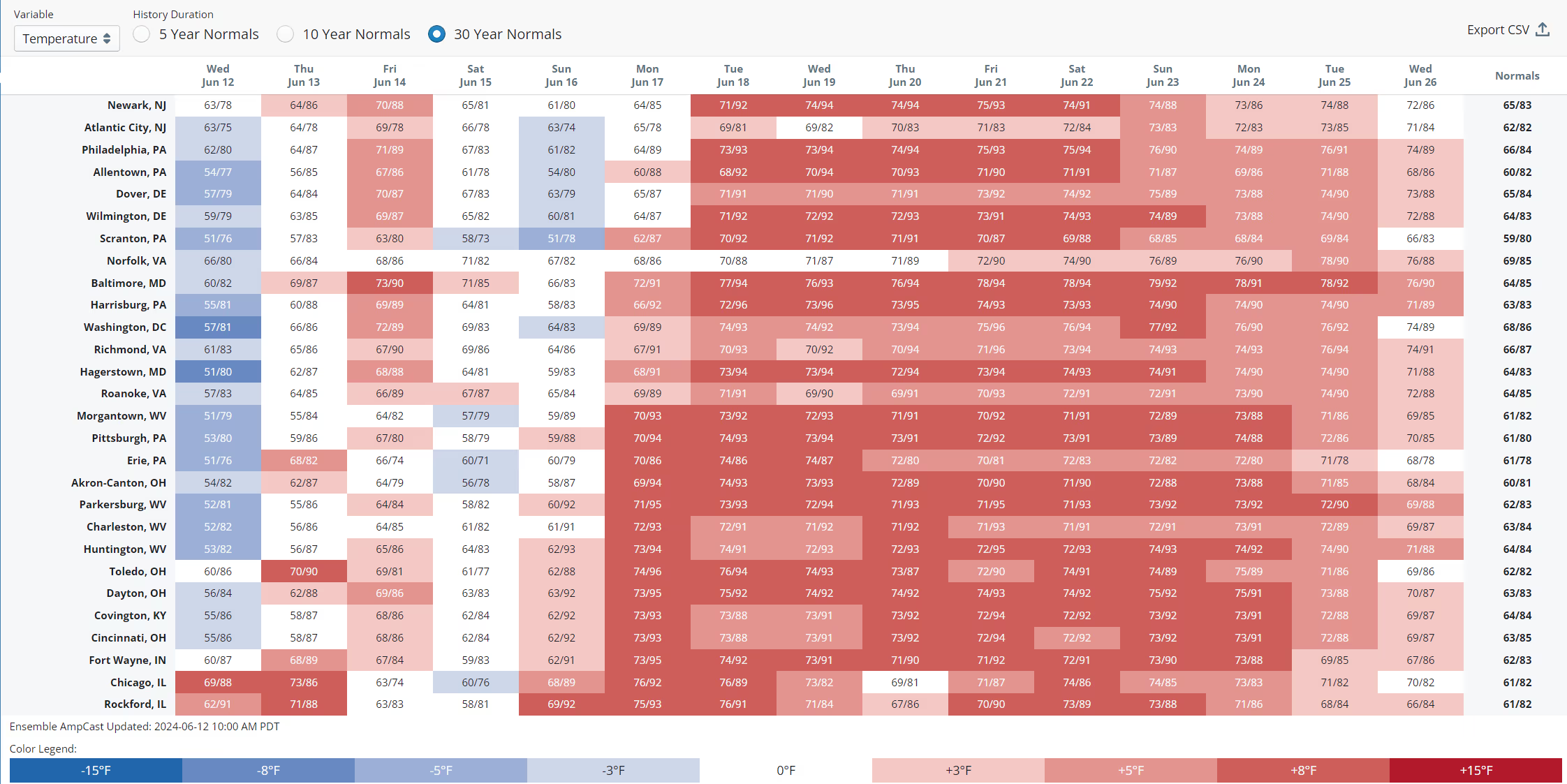

Shipham: Our platform produces demand forecasts through blends of four different weather models and 20,000 data collection points across the U.S. We adopted a multi-model approach after careful testing of the different paid and publicly available feeds. Ultimately, it’s what allowed us to generate the most accurate demand forecasts for different regions and for different types of utility customers. (Industrial customers have different demand profiles than residential customers.)

It's an exciting time to be in meteorology because the weather models are beginning to improve rapidly. The European model — European Center of Media Range Research (ECMWF) — has always been the best, but the brand-new National Blend of Models (NBM) in the U.S. is a radical improvement. The U.S. models are going from one-hour forecasts to 11-day forecasts, and eventually they will extend to six-week forecasts. We’re already seeing performance improvements from our blend of these models and the ones we get from three commercial weather vendors. It’s going to mean even better accuracy for our clients.

Do other demand forecasting firms use the same vendors?

Shipham: No. To the best of my knowledge, we’re the only firm purchasing weather data from multiple vendors. Also, I think I’m the only Ph.D. meteorologist on staff with a demand forecasting firm. Our competitors often use only the weather data produced at airports across the country. That’s a holdover from when it was still possible to do demand forecasting in very broad strokes on spreadsheets. But we are using AI to synthesize 20,000 weather data points across the country at a density of one kilometer in urban areas and five to ten kilometers in rural areas. This allows us to fine tune the demand forecasts in step with the various weather forecasts we input.

By comparison, some of our competitors don’t even source weather data themselves. They require their clients to supply it. That’s a low-cost approach for them, but if the data isn’t good, the forecasts can’t be. We’re hyper focused on weather because it's the primary element for building valuable demand forecasts.

To that point, what’s going on with weather in regard to climate change, and what do you tell clients about it?

Shipham: Ultimately, we don’t know what the long-term effects of ocean warming will be, but we do know that it puts more energy and moisture into the atmosphere, which leads to volatility. As someone who’s watched weather closely for a long time, I can confidently say that the volatility of weather events — and the frequency of extreme events — have certainly picked up over the last 10 to 15 years. We’ve had record years for hurricanes, forest fires, tornadoes and winter storms, not to mention heat.

My personal belief is that climate change isn’t an existential threat to humans. I believe we’ll find ways to adapt. Improving our ability to understand and predict the weather is one example of that. With better forecasting we’re able to reduce the risks — physical and financial —that’s caused by extreme and volatile weather.

.svg)

%20(3).png)

%20(2).png)

%20(1).png)

.png)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

%20(15).avif)

.avif)

%20(10).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)